Superconductors and superfluids lose nearly all of their resistance to electricity when chilled down to temperatures approaching Absolute Zero, and new research has devised a novel way to induce this effect in exotic matter.

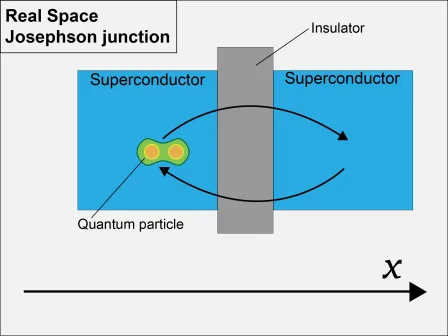

Superconductors and superfluids are a big topic in modern physics, and especially in the fields of quantum and condensed matter physics. Superconducting materials, namely those who lose nearly all of their resistance to electricity when chilled down to temperatures approaching Absolute Zero (-273.15 °C or -459.67 °F). “Superconductors have zero resistivity as opposed to regular materials,” explained Dr. Chuanwei Zhang, a Professor of Physics at Washington University in St. Louis. “One essential phenomenon in superconductors is if you put two semiconducting materials next to each other and sandwich an insulator in the area between them, electron pairs can move back and forth from one superconductor to the other.”

Superconducting materials and superfluid matter make amazingly efficient computing possible and can empower scientists to create certain types of magnetometers that allow for highly accurate sensing of magnetic fields. But it is their ability to enable fine-tuned metrology that brought Zhang to study these materials. Metrology, or the scientific study of measurement, may not be as high-profile as quantum computing or other possible applications for superconducting materials, but it is still an important focus area for modern physics. One of the reasons for this functionality is the Josephson effect, described above, wherein particles can flow between two superconductors across a thin insulating barrier, all while holding a correlation between factors like phase, frequency and voltage.

Zhang was part of a multinational team which studied the Josephson effect and its potential applications in modern sensing technology. The study, published June 7, 2024, in Physical Review Letters and selected as Editors’ Suggestions, focused on Josephson effects in a state of matter called the Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC). First theorized in the 1920s but not created in the lab until 1995, BECs exist when gases of bosons (one of the fundamental particles within atoms) are chilled to near-Absolute Zero. Zhang’s study is unique in that it focuses on a new way to produce Josephson junctions using BECs.

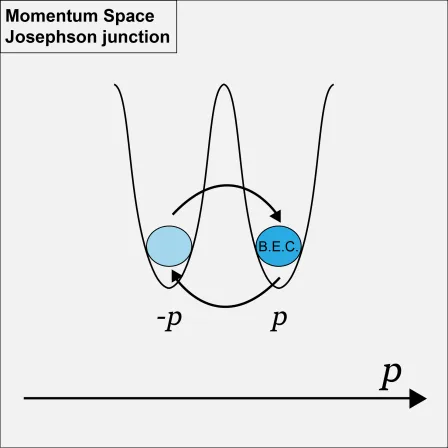

The traditional method of using Josephson effects is a “real space” junction. These are the standard affair where particles move between two superconducting materials across the thin insulating barrier. What makes the new method (also referred to as “momentum space” junctions) new is that it centers on two BEC superfluids that are located at different momentum states. “In real space electron pairs can jump across the junction through quantum tunneling and the particles exist in the same momentum space,” explained Zhang. “Whereas in a momentum space junction it must move between different momentum states, which effectively adds a new dimension to the transaction.” In other words, particles must move across the barrier through quantum tunneling even though they are not at the same momentum state.

“We began by confining rubidium-87 atoms in a high vacuum dipole trap,” said Zhang of experimental process. “We then cooled them down to the temperature of only a few nano-Kelvin. We do this because when atoms are this cold, they become less lively, allowing us to study them closely.” When the 87Rb atoms are cooled or “quenched” thusly, the properties of superconductivity/superfluidity are activated within them, among which is the function of Josephson effects between different 87Rb atoms in the BEC. From there, atoms begin flowing between the two momentum states of the BEC in the form of atomic currents through a laser-assisted quantum tunneling process.

This is the beginning of a so-called “superfluid stripe state” in the aforementioned 87Rb atomic BECs in the momentum space. This in turn allowed the scientists involved to design new exotic quantum matter and engineer quantum simulators utilizing momentum states as a synthetic degree of freedom. This is essentially a way of saying that they could use the superfluid 87Rb atomic BEC to simulate complex quantum states, thereby enabling a new dynamic in the world of quantum science. “One possibility is to look at this system and see how oscillation dynamics are impacted,” explained Zhang. “This includes the kind of interference experiments in real space, where you can use this for sensing the magnetic fields.”

In the long-term, this research will enable scientists to more accurately examine phenomena like magnetic fields, and it wouldn’t have been possible without plenty of cooperation. “One thing I want to say is that this kind of collaboration between the theory and experiment is very crucial,” said Zhang, pointing to the link that exists between different schools of physics. The paper is also a collaboration between multiple institutions, including Washington University in St. Louis, Washington State University, University of Science and Technology of China, the University of San Diego, and the University of Texas at Dallas.